Icefield Chemistry, by Donovan Dennis, Occidental College

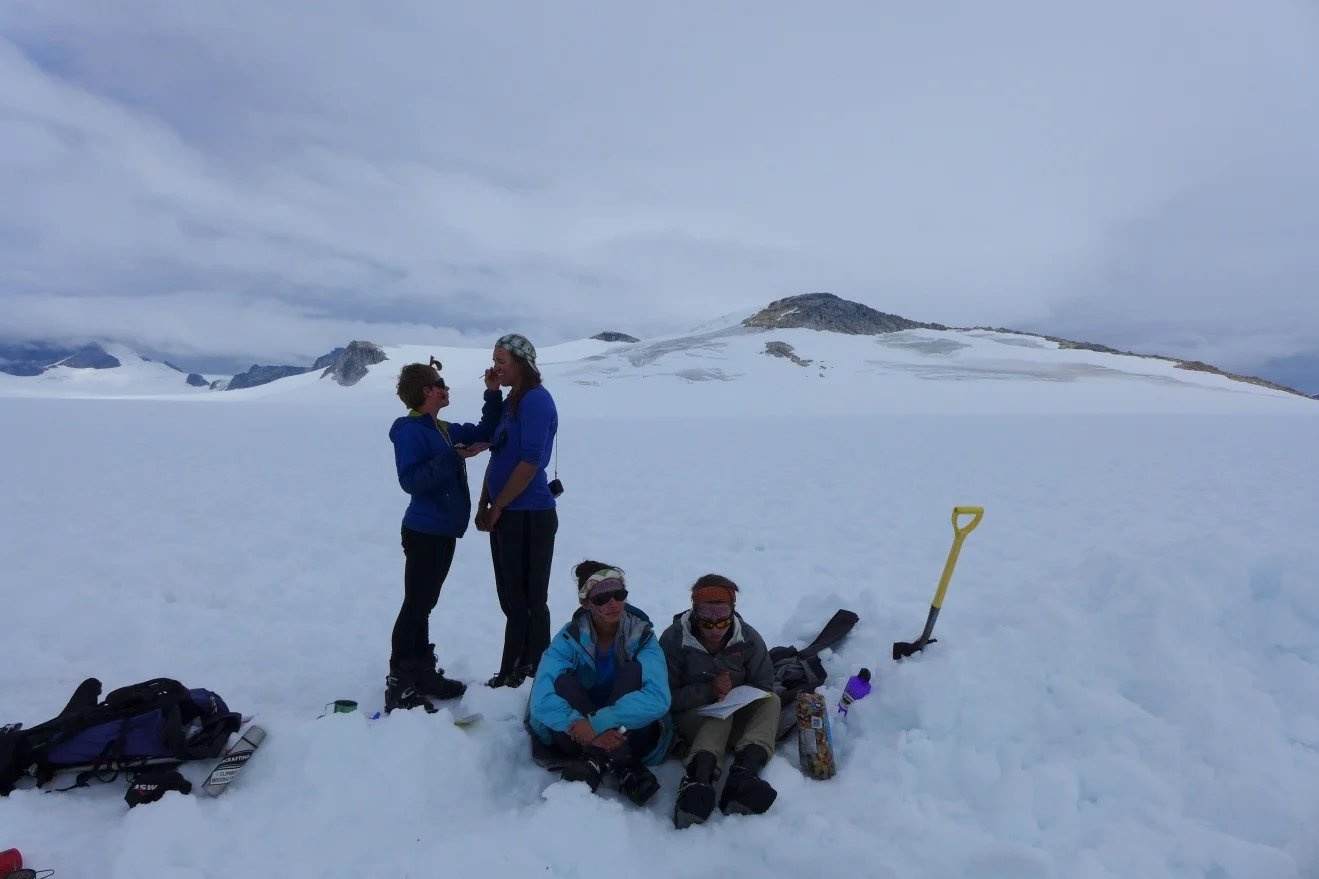

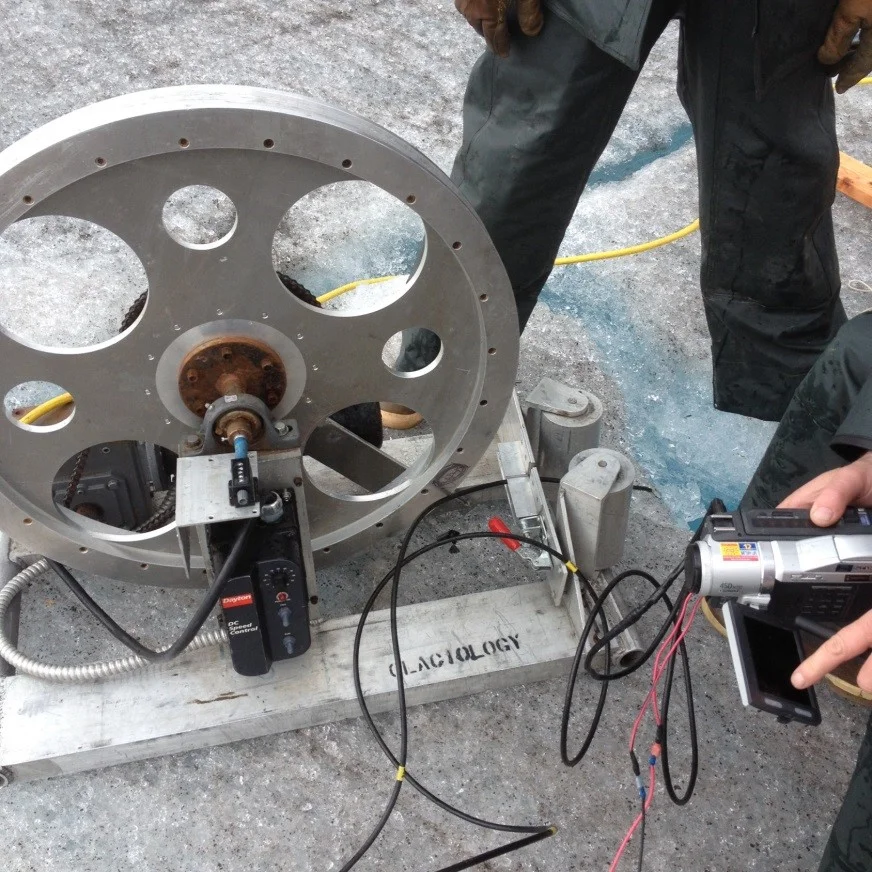

As our avid blog readers likely know by now, the chemistry of snow and ice evolves across the icefield, a function of the physical properties of oxygen and hydrogen isotopes. Students in the isotope research group investigate how the distribution of the isotopes change, from variation over several meters to variation over the entire icefield. Do isotope ratios change with elevation? How does rain change the composition of the surface snow? And the overarching question that we are all trying to address: is isotope analysis a useful measure for reconstructing past temperatures in this unique glacial environment? We are fortunate to have the tools and instructors available here on the ice to address these questions.

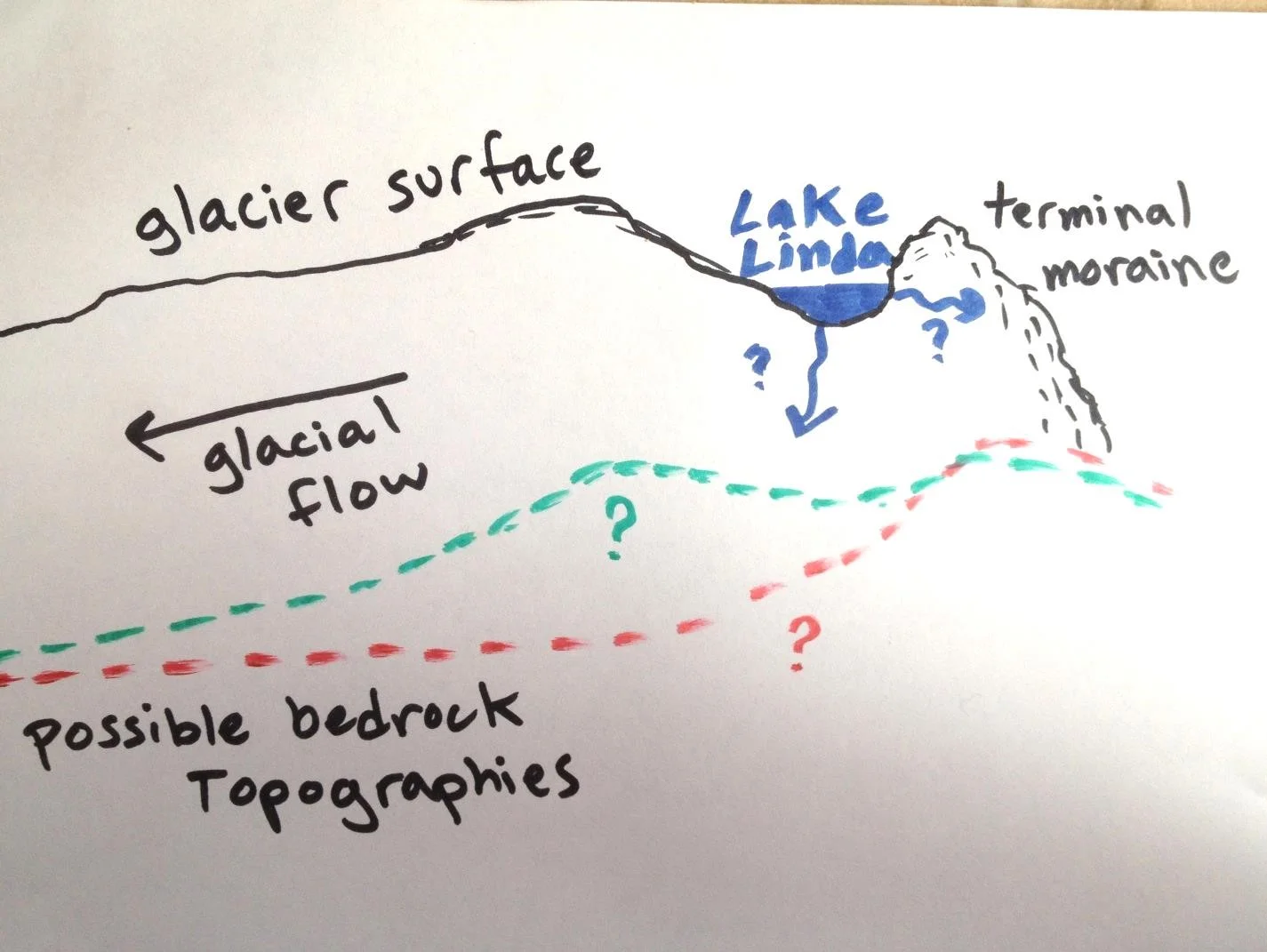

Isotope studies in other locations as well as the simplified Rayleigh model for fractionation[1] indicate that water molecules with heavy isotopes (Oxygen atoms with 18 neutrons) and Deuterium (Hydrogen atoms with two neutrons) fractionate (fall) first, typically nearest the source of the water. As the precipitation event moves farther away from its source, the clouds become more depleted in these heavy isotopes. In theory, we can track weather systems as they move across the icefield by measuring the concentrations of heavy isotopes in the snow and firn records. For more information on water chemistry across the icefield, numerous other blog entries tackle the Sisyphusian[2] task of explaining these projects and concepts.

June 23, 2015: Thirty-two JIRPers from strikingly different backgrounds coalesced in Juneau, AK, unsure of what to expect as they readied to ascend the ice. Like newly evaporated water, the composition of the group reflected its source: lots of variation.

“The people seem nice, and there is a healthy mix of intellect between us all. I’ve never known myself to be this obstructively shy before. I think it’s because everyone here seems to have something to say and there isn’t much else to offer in terms of conversation. Although after just a few hours here I can certainly see why so many are impressed by the rugged allure of Alaska. I’ve yet to be less than impressed by anything.”

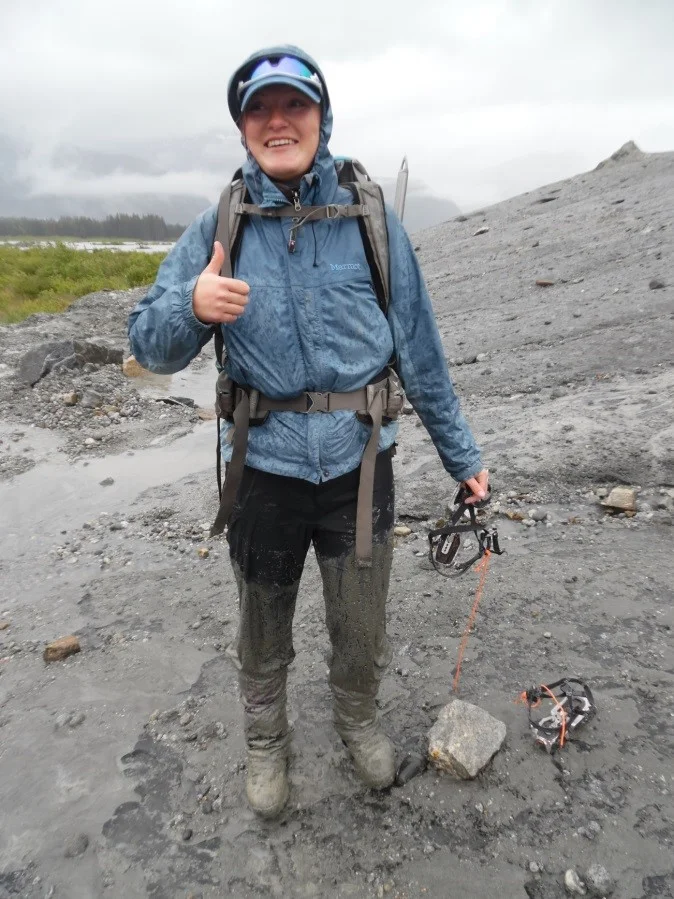

June 28, 2015: The ascent to Camp 17. The first isotope to fractionate out is the ego. Though we all come in with differing mountaineering experiences, fitness levels, and attitudes, the hike to Camp 17 sends the rugged individualist in us all packing.

“Around 7:35, we took off from the trailhead, and the weight of my pack became very apparent as we began the ascent up the first hill. It poured and poured, and my first fall came on a failing mud slope. That was a nice preface of what was to come. Had we not paid for this experience, I’m fairly certain it would have compared to a Vietnam jungle march. […] For much of the trip, I hiked/climbed/whined/cried with Isabel and Eric, two very mellow JIRPers from who knows where. We ascended much of the swamp together and became fast friends. As we exited the swamp, fully saturated in our boots up through the shins, I was unsure whether or not I could remember moving this quickly through the six stages as I grieved the health of my feet.”

Laurel Rand-Lewis (L) and Jeremy Littell (R) reach the Camp 17 ridge after the storied swamp ascent. All photos by author.

A cloudless view near the same rocks. Photo by author.

July 5, 2015: Our first best day on the icefield, and the emergence of a group mentality. The continued depletion of the luxuries of off-icefield lives and adaptation to our surroundings lent itself to the emergence of the JIRP 2015 family.

“We took our desserts to the Ptarmigan view rocks, and as Aaron’s guitar got louder we gathered a small group of singers and percussionists. Whereas the sunset on July 4 went out with a flourish of orange and red, the sunset of July 5 was a simple fiery orb dropping behind the mountains. In that moment, I never wanted to leave the icefield.”

Sunset on the fourth of July. The sunset July 5th was captured via good memories rather than good photographs.

As our group ebbed and flowed with the influx of faculty and staff, we came closer as a unit of 32. The inside jokes flourished in our microculture[3], intimidating the incoming faculty as they attempted to edge in. Individual backgrounds fractionated out as our group developed its own history—an entire past to draw upon for humor and inspiration. We started to evolve as a unit, growing together and becoming more similar as we moved across the icefield.

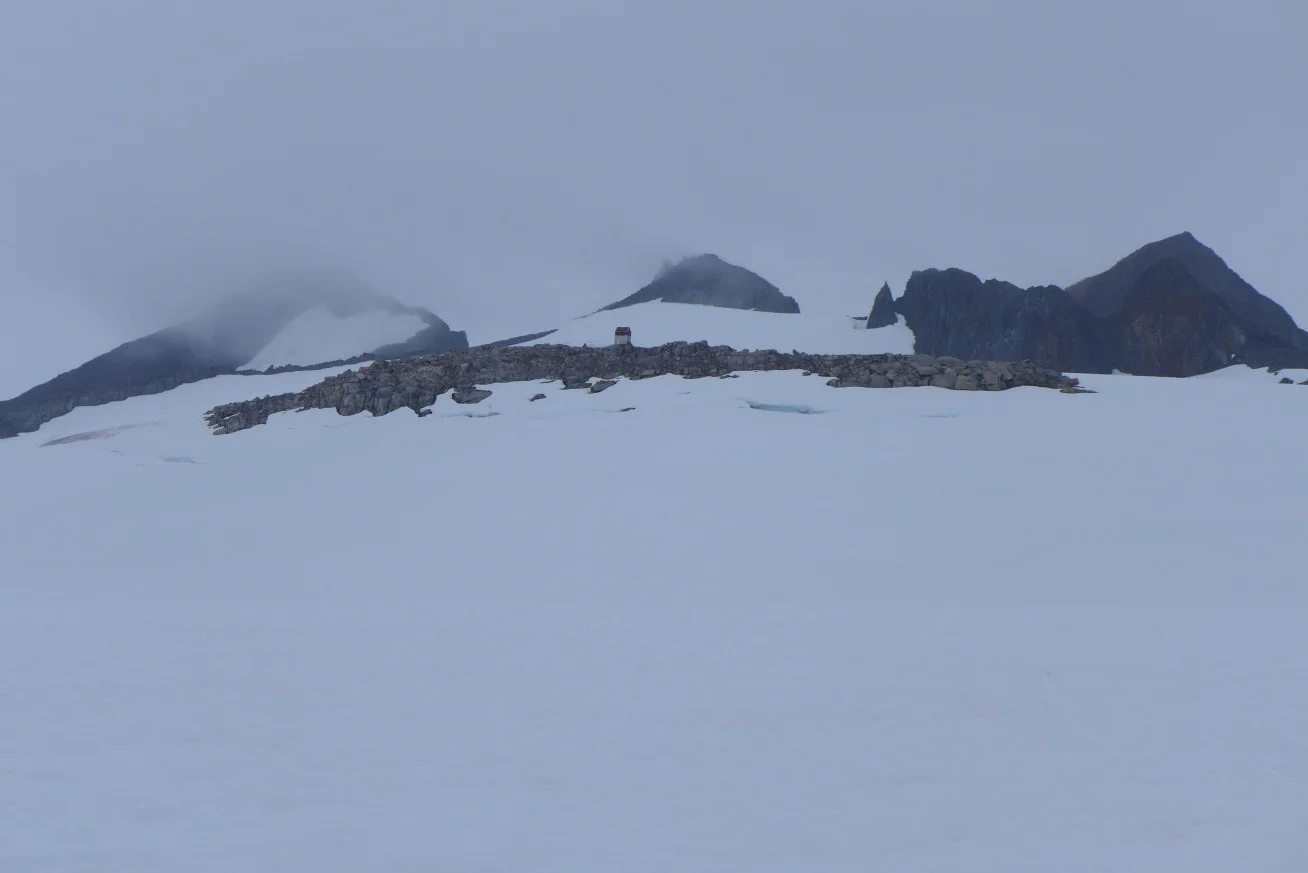

Moving across the icefield: the Norris Cache between camps 17 and 10.

The ping pong ball effect provides for beautiful views of the enveloping clouds.

July 30, 2015: Total immersion and acceptable uniformity. I began to understand the bigger picture of JIRP, the icefield, and came to know a version of myself unrecognizable six weeks before. Whereas in Juneau the survival of the group depended on the individuals, now the survival of the individual (or at least this individual) relied on the group.

“I now know that I will return to the icefield. It’s calming almost, accepting this certainty. To be in the presence of something so much more than me, it’s more than inspiring—it’s possessing. The landscape grips its beholder with an iron clench, refusing to budge. It’s hard to breath. Camp 17 was new; Camp 10 was vast; but Camp 18 is aggressive. Alone, these hideaways are but individual camps on an icefield, but together they complement each other with un-named harmony. I have to be back.”

The view from Camp 17.

The view from Camp 10.

The view from “The Cleaver” at Camp 18.

This wasn’t an easy journey. It was physically exhausting. It levied a tax on emotions and interpersonal skills, and it forced us to question ourselves as we battled frigid “summer”[4] temperatures, unrelenting wind, and other undesirables[5] associated with the icefield. But now, as we progress farther away from Juneau and rapidly encroach upon Atlin, we rely less on ourselves for perseverance and support, and more on the group and environment to sustain us. Like the ice under our feet, our chemistry has changed. We are friends and family, the FGERs in us all understood only by each other.

Celebrating the completion of Llewellyn Pit 2 with the American and Canadian flags looking on. From left to right Allie Strel, me (Donovan), Jeff Gunderson, Jacob Hollander, and Tristan Amaral.

[1] See blog entry by Jutta Hopkins- for more information regarding Rayleigh distillation. Also, Google is a thing.

[2] Sisyphusian: an immense and infinite task only able to be undertaken by the most heroic amongst us.

[3] Microculture: A culture that develops within a small, seemingly abandoned group via total isolation from society and popular culture.

[4] I found myself planted in the rocks at Camp 8 several mornings ago, having slipped on the ice layer that enveloped the rocks overnight. The icecap over the water supply buckets measured in at one inch thick.

[5] For example: skiing downhill with a 50-pound backpack, avoiding baths and showers for months on end, undercooked spam, having more blister than foot après ski, and the “ping pong ball” effect.