Taku Terminus

Mickey Mackie, Harvard University

Isabel Suhr, Lewis and Clark College

Mickey:

The rotors picked up speed with a deafening roar. I felt a wobble, and the helicopter was lifted into the air. Isabel and I were on our way to the Taku Terminus to assist a research team with field work. I was in the front seat. The window stretched to the floor and I could see the Taku Glacier beneath my feet. Camp 10 disappeared in the distance.

We flew low to the ground and crossed over the section we skied across to get to Camp 10. It was now streaked with ice and crevasses.

Crevasses on the Taku Glacier. Photo: Isabel Suhr

A wondrous sight appeared on the horizon: trees, thousands of them. I basked in the magnificence of the first greenery I’d seen in weeks. I was still in shock when we touched down in camp, our home for the next week.

Isabel:

Camp life at the Taku Terminus field camp was very different from life on JIRP. Instead of a permanent camp, we each had a small tent to sleep in, plus a large communal tent for cooking and one for gear storage. We camped just past the terminus of the glacier, on flat exposed sediment between Taku Inlet and the outlet streams from the Taku Glacier. It was very strange to be among plants again!

Camp at the Taku terminus. Photo: Mickey MacKie

There were thirteen people at camp including Mickey and I, and we worked on a variety of different projects on the Taku terminus. Jason Amundson, from University of Alaska Southeast, was in charge of the camp, and the other scientists were all from UAS or University of Alaska Fairbanks. In addition to the scientists, Jason’s wife and four-year-old-daughter were at camp, which made our mornings and evenings really fun.

Mickey:

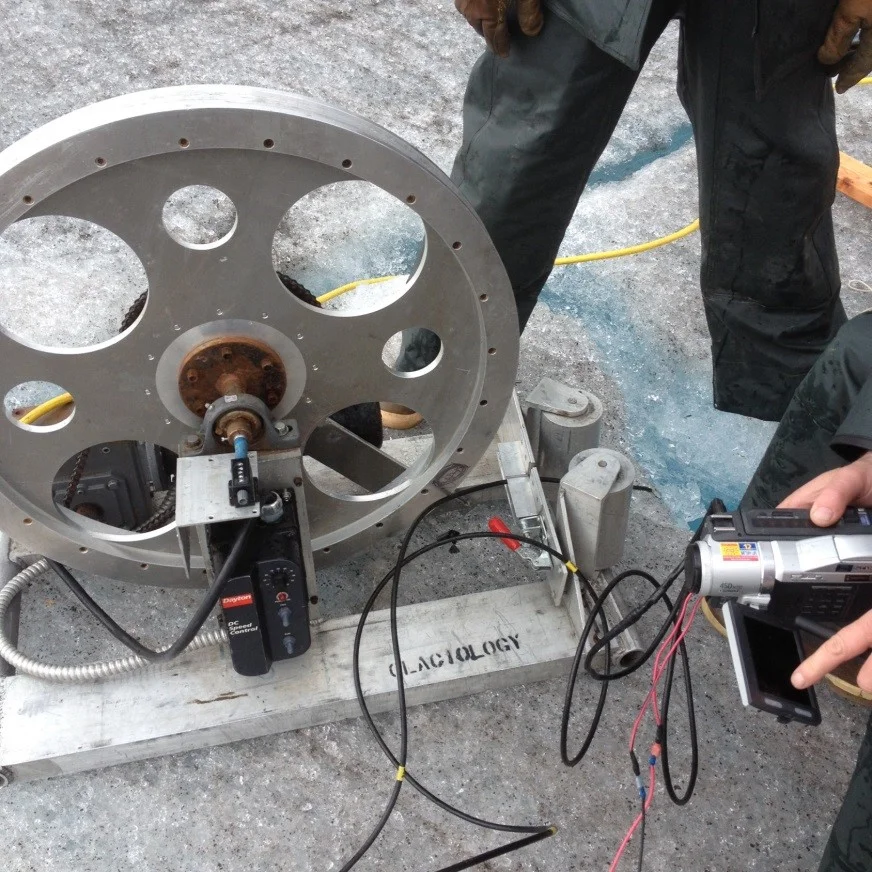

15,000 lbs of gear, a glacier, and three crazy scientists are what you need to drill a borehole in the ice. Martin Truffer from University of Alaska Fairbanks led the operation. The boreholes were made using pressurized steam. Water was heated in a container called the hot tub and was fed through a tube into the hole.

Lowering a camera down the borehole. Photo: Mickey MacKie

These holes can be used to get sediment samples, do dye tests, or study glacier deformation. Martin put a camera in the hole, and we were able to see a subglacial stream. It was exciting to see how technology is used to learn more about glaciers.

Isabel:

The project Mickey and I did the most work for was a seismic survey. Jenna, a grad student from UAF, was the lead on the project and Mickey and I, and another undergrad from UAF, were field assistants.

Seismics are a good way to get information about the bottom of a glacier and what is below it. To do a seismic survey you need seismic waves to measure, whether they are from an earthquake or from a manmade explosion. We used a Betsy gun, which fires blank shotgun shells. To create the seismic waves, we bored a hole a half a meter or so into the ice, then placed the Betsy gun in the hole. To fire it, we hit the top of the gun with a sledgehammer, which then fired the blank at the bottom of the hole, creating seismic waves. It was quite the explosion!

To get information from the Betsy gun explosions, we used two types of instruments to measure the seismic waves we created—geophones and geopebbles. Both are seismometers: they measure vibrations in the ground. The geophones are single-component seismometers, which means they have one sensor to measure seismic waves. The geophones then all connect to a cable, which relays their information back to a computer. The geopebbles are a little different: they are three-component seismometers, so with their three sensors they can track the direction of movement of the seismic waves. They also have a built-in GPS and can transfer information wirelessly. We used a combination of geophones, for dense sampling over the point of interest, and geopebbles, for measurements farther from the shot locations.

Mickey placing the geophones. Photo: Isabel Suhr

Over the three days Mickey and I helped with the project, we started by checking out the seismic line we planned to use, then placed the geophones and geopebbles in the ice, then finally fired shots from the Betsy gun at intervals along the line. It was pretty cold and wet work, but we really enjoyed getting a chance to see what conducting a seismic survey was like!

Mickey:

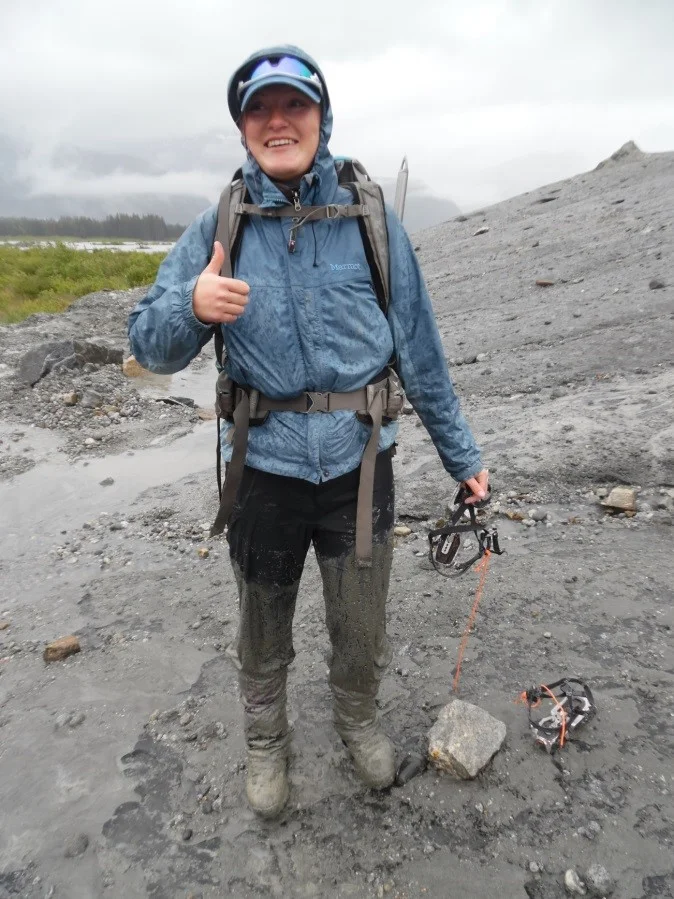

Through mud, over moraine, to the ice we strode.

We went in a line – I was at the end of the row.

I walked across what seemed like solid ground

And found myself shifted several feet down.

I felt the ooze seep into my pants

And realized that I was stuck in quicksand.

As I stood immobilized in that murky pool,

All I could think was, “This is so cool!”

Strong arms grabbed me, and with many a tug

I was finally lifted out of that mud.

Dear reader: if in quicksand you ever should fall,

I hope that unlike mine, your pants don’t have a hole.

Post-quicksand. Photo: Isabel Suhr

Isabel:

Getting back to JIRP from the terminus turned into quite an adventure. After a day of weather delays, we changed plans to go through Juneau on the way back to Camp 10 rather than straight to Camp 18. To get to Juneau, we got a lift from Brian, a very kind airboat operator, across the inlet to his airboat base, where he had a helicopter of tourists coming in from Juneau. The airboat ride was amazing—since it has a giant fan instead of an outboard motor, we could go into very shallow water without risking running aground. On the way back to the airboat base, we took a look up the Norris River to the Norris Glacier, which had a calving front. It was very cool to see the icebergs and hanging blocks of ice that were about to fall! We took another look at the calving front from the air on the helicopter ride back to Juneau too.

Isabel in the airboat. Photo: Mickey MacKie

The calving front from the air. Photo: Isabel Suhr

Being in Juneau was strange—we had gotten so used to life on the icefield that being in civilization again was a shock. Luckily, after a few hours we could get on a helicopter to Camp 10 to rejoin our friends!