Part 1:

Little Details

Kellie Schaefer, Michigan Technological University

One of the best ways to document a specific person, place, or thing is to compose a field sketch. Field sketches are extremely useful on the icefield for a number of reasons. They help to create a record for future analysis. For example, a field sketch of a specific icefall or cirque glacier can be compared with another field sketch or photograph from a different time to see how much change has occurred. In addition to providing an image, field sketches include a set of notes describing who did the sketch, where they were, what the weather conditions were, when they composed the sketch, and why they decided to sketch a particular subject. Unlike a photograph, these specific details can be included for future reference. Field sketches also help the composer to record their memories of the subject that they are sketching. Much more time, effort, and observation are put into a field sketch than into a photograph. Little details must be taken into account. The scale of the sketch must be proportionate to the actual object. This forces the composer of the sketch to deeply analyze the “big picture”.

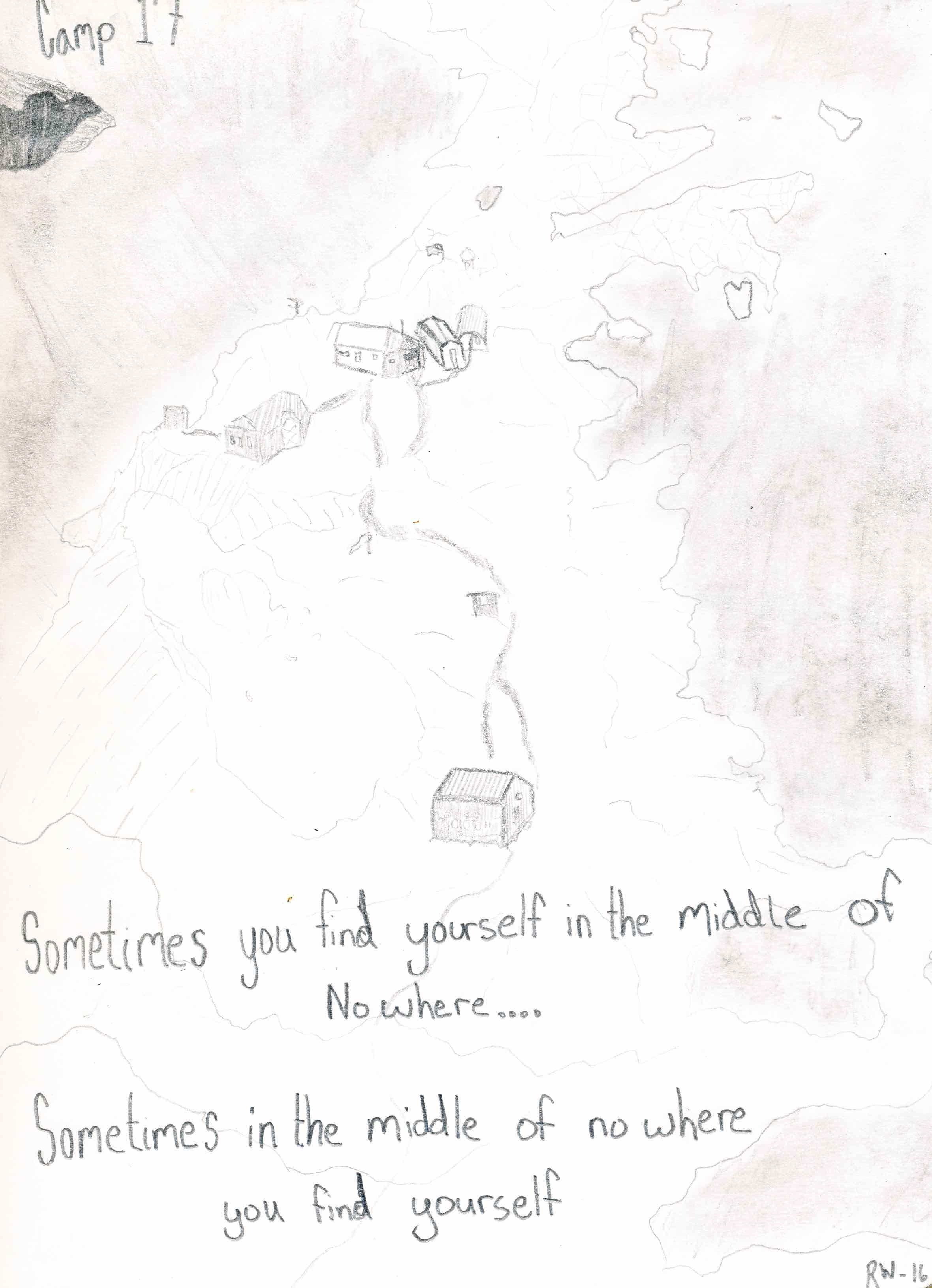

This aspect of analyzing the “big picture” is why I enjoyed field sketching on the icefield so much. Most of the time, I would ski or hike past the most amazing sights I’ve ever seen, and I didn’t take the time to really look at these sights. I would snap a photograph, pause a moment to take in the scenery, and continue on with what I was doing. When I decided to sketch something, it really made me analyze what exactly I was drawing. Where did this rock slope meet the glacier? How was this peak situated with respect to its surroundings? How many cracks were there on the right face of a particular Taku Tower? Little details that I would most likely have overlooked were suddenly seen. I can still go back to my memories of the places I sketched and remember them as if I’d only seen them yesterday. I can still see the bush planes that flew past us on Vesper Peak as a group of students sat on top, quietly contemplating the layout of Camp 17. I can still feel the intense sun that beat down on Camp 10 as I sketched the Taku Towers. Sketching put me into a near meditative state. I would become so fixated on what I was sketching that I couldn’t think about anything else.

While field sketching provides us with a way to compile scientific observations, it also enables us to get a good look at our surroundings and observe the little details that would normally be overlooked. Some people may be thinking that they need to be an artist in order to make a good field sketch. Being an artist is not necessary, because the purpose of a field sketch is not to create a masterpiece, but to record with pencil and paper your experiences and how you are interpreting them.

Part 2:

Sketching a JIRP Field Season

Annika Ord, JIRP Senior Staff Member

June 30, 2016

Watching the waters rise during the now annual jökulhlaup, a glacial outburst flood, at Mendenhall Glacier visitor center. JIRP students take field notes in our first field sketching outing of the season.

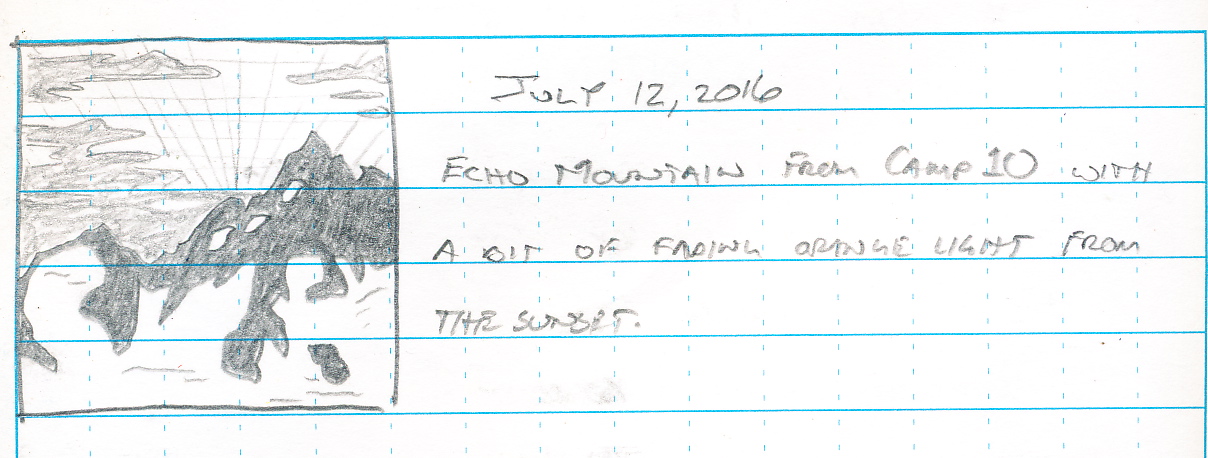

July 9, 2016 Observing the route to C-10 with anticipation. Like 2015, the snow cover was particularly low, and we'd have to transition multiple times between snow and ice before reaching the Norris Cache and a well deserved nights sleep in the village of tents.

July 16, 2016

We stumbled upon this gem of a lake while exploring Ivy Ridge for vascular plants with the botany project group, otherwise known as Portable Plant. Sapphire blue and filled with icebergs, it lay like a gem between the talus slope and a blue ice face of the glacier.

August, 2016

Waiting at the inlet for Archie, soaking up the last moments before Atlin and the return of showers, dogs, and four-wheeled mobiles.

Part 3:

Field Sketching and JIRP

Matt Beedle, Director of Academic and Research

At the outset of the eight weeks of JIRP, many participants begrudge the leaving behind of screens and digital connectivity. Strangely, this forced "isolation" feels foreign. But upon emerging in Atlin, it may well be one of the things that we JIRP participants miss most.

Dr. Maynard Miller (JIRP co-founder and long-time director) is famed for saying, and guiding JIRP based on this maxim:

“We bring students into Nature, and that makes all the difference.”

JIRP, however, does a bit more than "bring students into Nature" - it fully immerses students in the wilderness of the northern Coast Mountains. This immersion, I feel, is crucial to the power of JIRP, and the power of wilderness experience in general. Even while immersed in such an experience, however, it's easy to gloss over your surroundings. To take a picture and make a promise to revisit the landscape at a later date (a promise unlikely to come true). In many years with JIRP, and on my travels with family and friends, my only regret is that I didn't slow down even more. Field sketching affords this slowing down, an opportunity to study, admire and learn from the landscape, and also to cache the memory in our internal hard drives for later recollection. Quoting Locke (1989) in their seminal review of "Learning in the Field", Mogk and Goodwin (2012) write:

“Having to physically move from place to place in the environment requires students to slow down their engagement with the subject of interest, take time to talk with mentors and peers about observations as they emerge, and have time to reflect on their work to gain deeper understanding.”

This slowing down, taking time, and having time is central to the JIRP experience. JIRP has benefited greatly from having artists play an integral role, artists such as Dee Molenaar, Maria Coryell-Martin, Annika Ord, Kellie Shaefer and more. We are excited that field sketching has grown in prominence in recent years under the guidance of Annika, and to announce that the role of art and science communication is set to expand for JIRP 2017 (more on this soon). In the mean time, know that JIRP and its participants aren't the only beneficiaries. Sitting down, breathing, looking, seeing, sketching are available to all. Grab a pen and paper. Slow down. Breathe. Sketch.

Left to Right: The toes and sketches of JIRPers after a pause for observation and reflection at Mendenhall Glacier (Photo: M. Beedle). Annika Ord sketches Camp 18 and Vaughan Lewis Glacier (Photo: A. Pope). The sketches completed by JIRPers during the 2016 "JIRP Olympics" at Camp 17 (Photo: M. Beedle).

References:

Mogk, D. W. and Goodwin, C. 2012. Learning in the field: Synthesis of research on thinking and learning in the geosciences, in Kastens, K. A., and Manduca, C.A., eds., Earth and Mind II: A Synthesis of Research on Thinking and Learning in the Geosciences: Geological Society of America Special Paper 486, p. 131-163, doi:10.1130/2012.2486(24).