Sciencing Lake Linda, or, “We’re Not English Majors Here”

July 31, 2015

Jolon Timms, Reed College

The Popemobile (Ph.D. in glaciology, currently working on a post-doc at University of Washington and CU Boulder, and JIRP faculty, Allen Pope) looked nervous. His bowtie was slightly crooked like Owen Wilson’s smile, minus the luxurious hair. Kiya Riverman, Allen’s discussion partner, (opponent on the opposite side of the ring) a Ph.D. student studying glacial hydrology at Penn State University, and JIRP faculty, was keeping her cool. The two, standing at one end of the Camp 17 cook-shack, were about to challenge each other’s hypotheses regarding the discharge of water from Lake Linda.

Lake Linda on the Lemon Creek glacier, mid-drainage. Photo by Joel Wilner.

The lake, a dear one to JIRPers, sits nestled against a large mound of sediment deposited many years ago by the Lemon Creek glacier (technically called a “terminal moraine”) in the region on the glacier where snow cover exists perennially (called the “accumulation zone”). Last century, Lake Linda was two smaller lakes every summer: Lake Linda and its smaller cousin, Lake Lynn, which sat a short distance above Lake Linda. Before Lynn merged with Linda, daring JIRPers crawled through the empty ice tunnels which allowed Lynn to drain into Linda every year. Now Linda drains within the timespan of a few days in the middle of every summer, often while bright-eyed and not-quite-yet-burnt-to-a-crisp JIRPers inhabit C-17. However, this year Linda started draining while the group was at C-17—and then stopped after two days of draining (see above photo), thus sparking intense debate among faculty and students as to why Linda stopped discharging water mid-drainage.

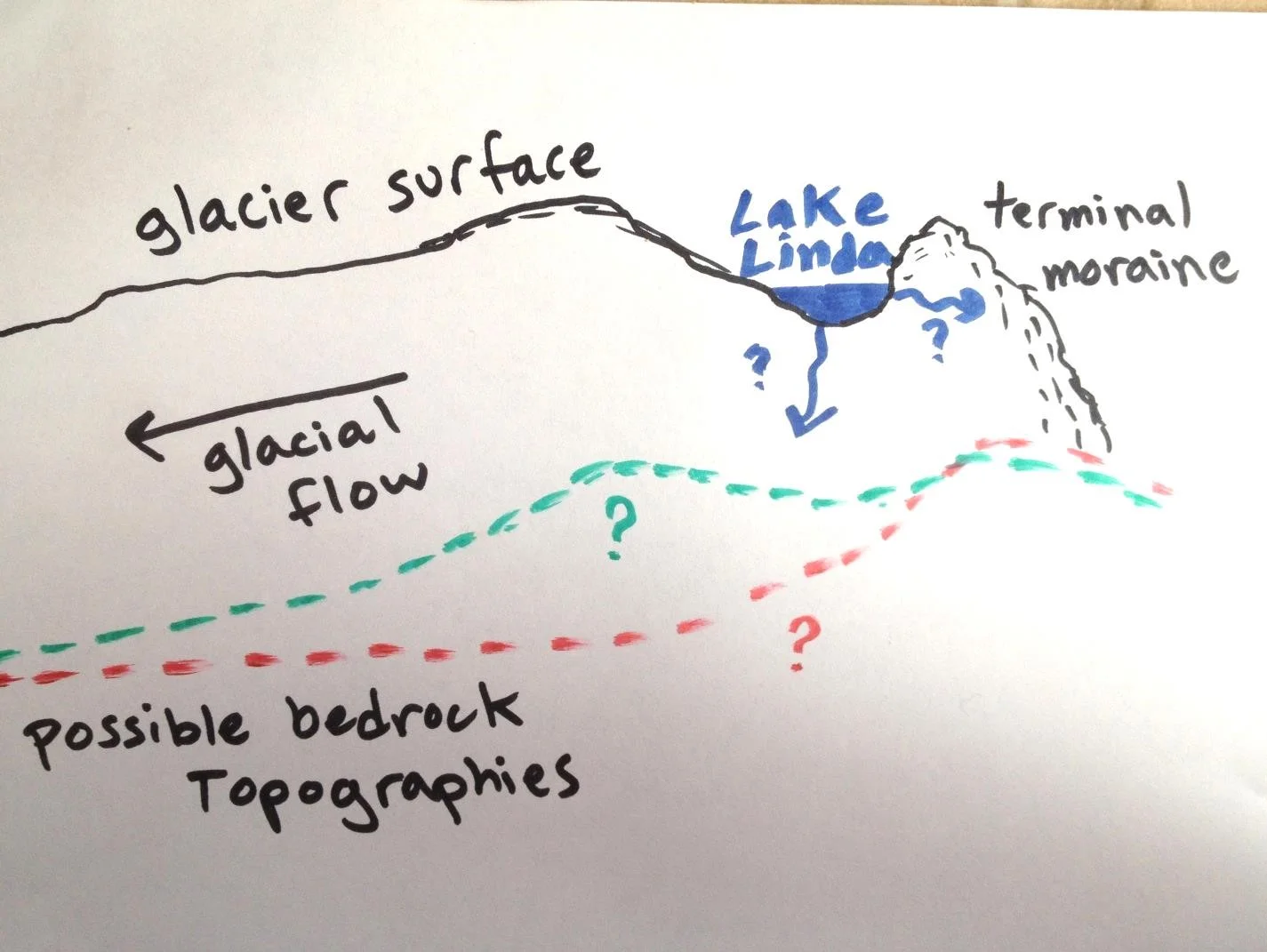

Sketched profile of the Lemon Creek glacier. Question marks indicate unknown directional flow of lake drainage (blue lines) and possible bedrock topographies (dashed red and green lines).

The discussion in the cook-shack commenced with level-headed Kiya explaining that she thinks Linda stopped draining mid-drainage this year because the lake was actually draining through the terminal moraine against which its south side lay, not through or along the glacier bed as most supraglacial lakes drain. (Note: none of the following quotes are exact).

“A supraglacial lake will start to drain when it overflows its icy embankments, fractures the ice beneath the lake due to the immense pressure exerted by the water, or finds or creates an englacial stream through which water may flow. The more water that flows over ice, the quicker the ice will melt, creating a larger channel or tunnel through which more water can flow, melting the ice quicker and so on until the lake has drained completely,” Kiya said confidently.

Lake Linda close-up, with terminal moraine on right and Lemon Creek Glacier on left. Photo by J. Wilner.

“However, because Linda stopped draining after only two days, I hypothesize that Linda is in fact draining southward through the moraine and not through ice. Were Linda draining through ice, it would drain increasingly faster until Linda was no more. Because Linda’s drainage has been slow and halted, I believe Linda has been draining through the moraine, where a sediment channel could have collapsed or otherwise blocked the flow of water and thus stopped the drainage of the lake.”

Suddenly Allen Pope jumped in, attempting to save his reputation “Just wait one fancy second. It is indeed possible that the lake is draining through the moraine. However, it is more likely that the lake is draining through or underneath the glacier. We don’t know the bedrock topography below the glacier. It could very well be the case that Linda stopped draining because the bedrock topography restricted the flow of water below the glacier.

The Popesicle continued to spout excellence. “Moreover, it could be the case that the hole through which the lake is draining has been blocked by one of those large seracs (large chunks of ice floating in the lake). Sure, the blocks of ice are floating on the top of the lake, but they are large enough to reach a hole in the lake bottom.”

Allen Pope in bowtie and top hat and Kiya Riverman in purple. Photo by Blaire Slavin.

Alf Pinchak, longtime JIRPer and expert glaciologist, jutted in at this point. “Years ago, the perimeter of the lake was covered in snow and ice and you could ski to the top of the moraine, straddle it, and hear water flowing on both sides.” Kiya threw a smirk towards Allen and he gulped it down reluctantly. His hypothesis was under pressure.

“To be fair, there are many crucial details that we simply don’t know,” Allen protested. “In order to answer the question of Linda’s drainage, we would want to measure drainage rates during the summer in the outlet streams below the Lemon Creek and the terminal moraine. Additionally, we could call up Seth “I will GPR the entire Earth” Campbell to run a ground penetrating radar (GPR) over the Lemon Creek to get a better sense of the glacier’s bedrock topography. These tests, in combination, would allow us to get much closer to answering the present question.”

“Great scientific suggestions, Allen.” Kiya was trying boost Allen’s morale. “We might also add some dye to the lake to see clearly where the water goes when it drains. And in addition to GPR, we could use seismics, the results of which we could compare to those of the GPR survey. If only we had two weeks and tens of thousands of dollars.”

Lake Linda was thoroughly “scienced”. Not only did everyone in the cook-shack learn a fair amount about Lake Linda, the discussion also reflected the best of the scientific process in real time as performed by real scientists. What could have been an intimidating intellectual brawl turned out to be a deeply important demonstration of what the scientific community does best. As Allen left the cook shack, I noticed that somehow, perhaps by the magical force of good science, Allen’s bowtie was perfectly level on his scrawny neck .