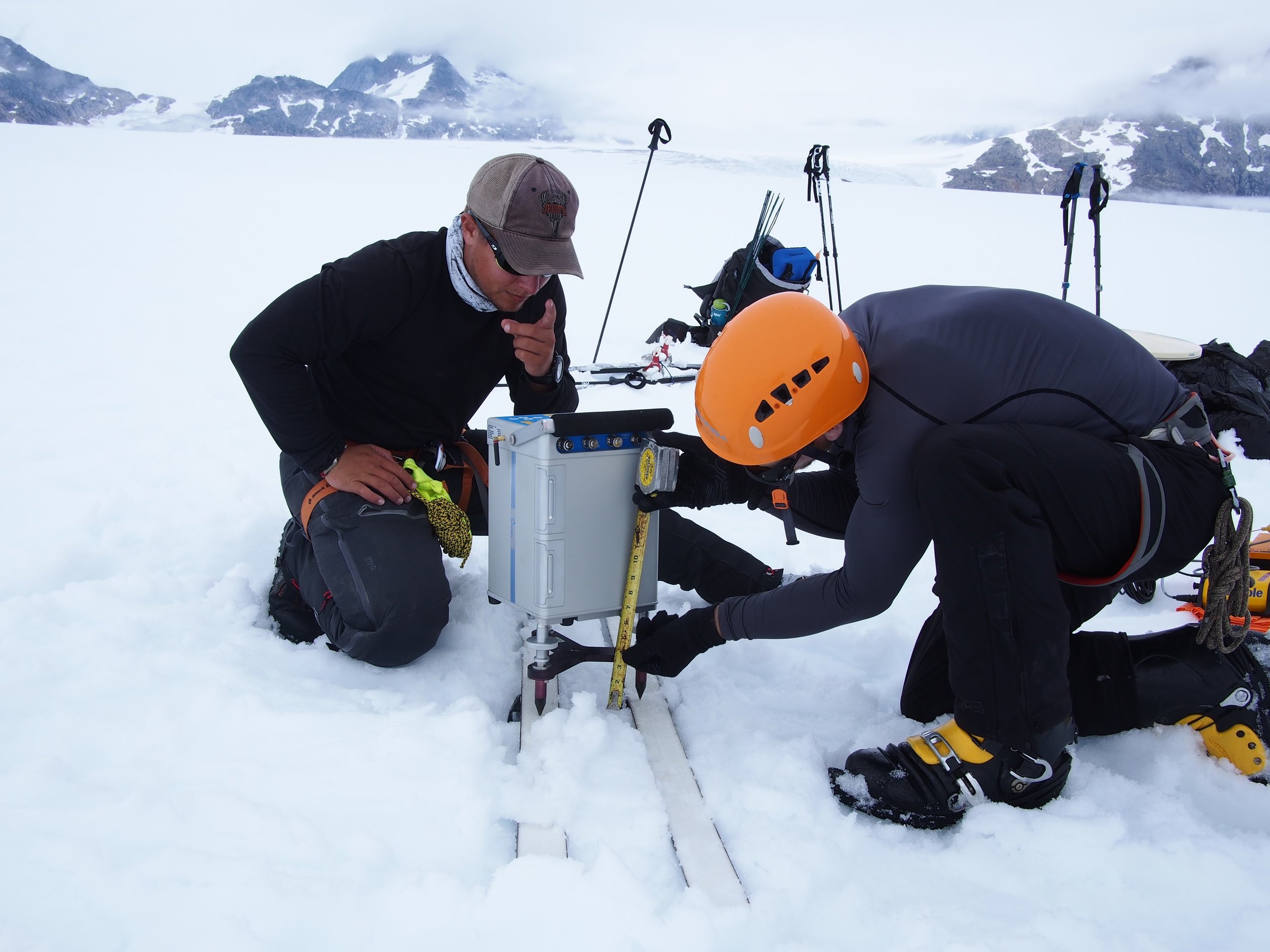

By Gavin McNamara, Dalhousie University

After a hectic day of packing, errands, showers, last minute phone calls, and final tastes of civilization, we were ready to hike to Camp 17. This is where our home base was for the first 10-12 days on the Juneau Icefield. Our ten person trail party got to the trailhead and began the long hike with some speed as we knew the trailing group, led by Ibai’s lightweight and fast mentality, would be at our heels. We were certain Ibai [JIRP's Safety Manager] meant business as Christoph heard Benjy exclaiming “I poured out half my GORP (Granola-Oats-Raisins-Peanuts) for you!” when Ibai was checking the weight of bags the night before.

So, after 4-5 hours of efficient movement through forest and steeply angled swamp, we came across an unforeseen obstacle: a large black bear munching on an unlucky goat. To top off this Wild Alaskan scene, there were bald eagles screeching and circling above the valley.

The bear eats the goat. Photo: Gavin McNamara.

Other goats look on. Photo: Gavin McNamara.

The black bear stood up over the goat and stared directly at us, chunks of bloody white hair dangling from its mouth. As it was clear the bear had no intention of deserting his coveted goat, we retreated to the ridge to decide upon a course of action. We were bound on both sides by high angled forest and rock bands, so we made the decision to wait for the other two trail parties before making any moves. We felt that there was safety in numbers, so with our larger group of 25 we traversed as high as possible above the bear in order to regain the trail. Luckily, the bear appeared to be in a complete food coma; we safely passed while the bear had dreams of his goat. The rest of the hike was spectacular and we welcomed our new home in the clouds at Camp 17 with cold and open arms. We relished in the comforts of our new rugged abode, happy to have made it past the bear and eager for our own hot meal.

The group successfully past the bear. Photo: Gavin McNamara.