By Amy Towell, University of Toledo

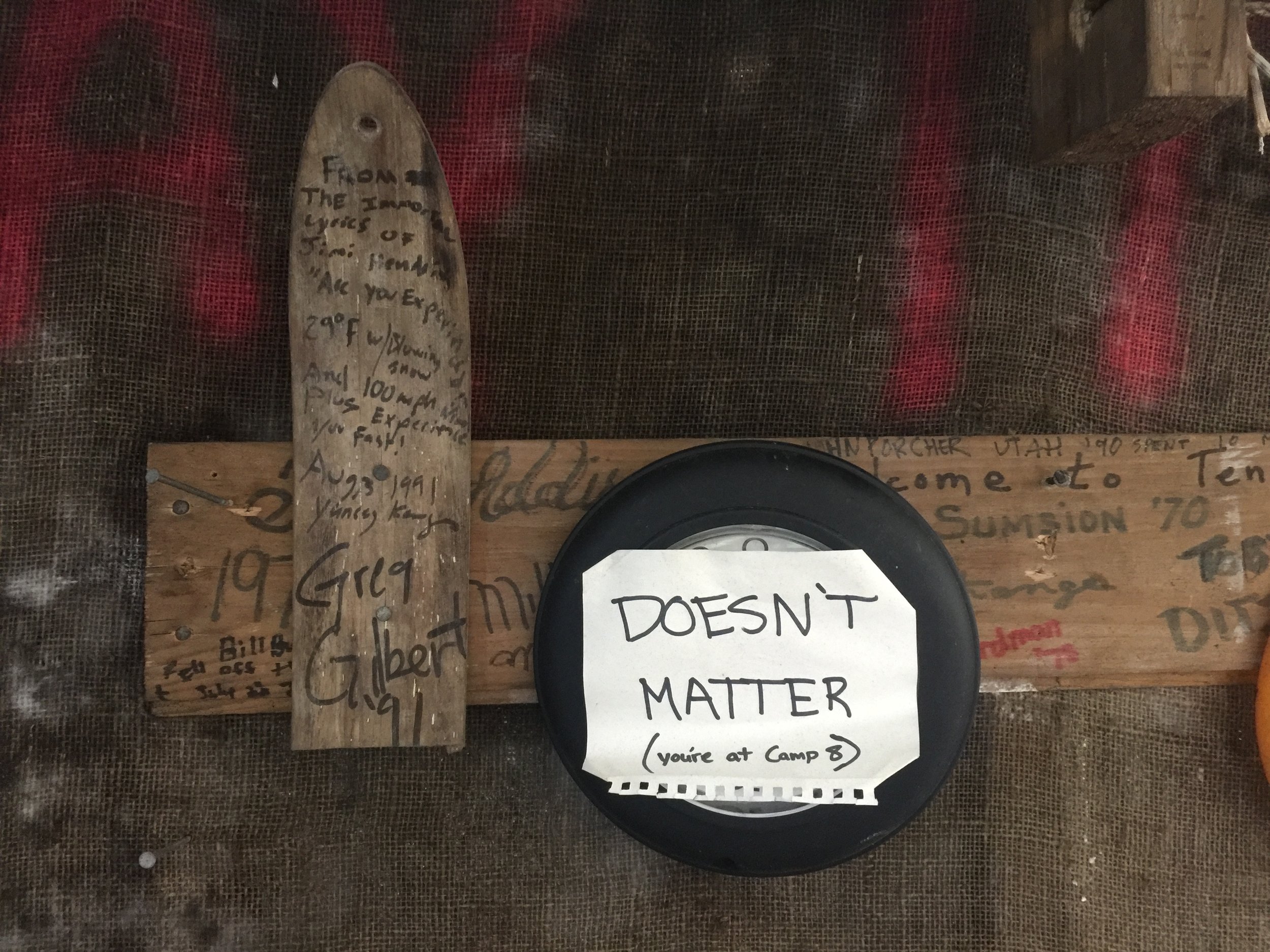

Camp 8… A place for rest, relaxation, the occasional radio relay and experimentations in waffles…

Camp 8 has one sole purpose: to relay radio calls between the Juneau Base and Camp 18. While the entire expedition is based out of Camp 18, groups of four take turns being stationed at Camp 8 for two nights. It isn’t a terribly long ski (usually four hours) between Camp 18 and Camp 8, but it took us a bit longer due to route conditions on the ridge approaching Camp 8. The snow bridges covering the giant bergschrunds [crevasses that extend all the way through the glacier to the bedrock] and crevasses had collapsed, which made taking the original route dangerous. We scouted a new route with help from Gavin, who was manning the radio at Camp 8 and could see the hazards from above. The other three inhabitants of Camp 8 were also helping on the ice by scouting the new route from the opposite direction. We had to probe extensively, which slowed our pace considerably, since the new route put us between two very large crevasses.

Our rope team, probing our way slowly and safely through the maze of crevasses. Photo: Amy Towell.

A view from the top of Mount Moore looking down on C8 and the route through the bergschrunds and crevasses. Photo: Amy Towell.

After an hour of nerve racking zigzagging and navigating over crevasses, we made it to the safety of our new abode on the slopes of Mount Moore. My feet were happy to arrive and be able to rest for a few days, and the group, as a whole, were excited to eat nothing but waffles for the duration of our stay; Camp 8 has the only waffle maker of the entire icefield! Our mission: eat more waffles than the previous group, which ate 14 in total.

Blisters galore. I have been anti-croc for many years, but caved on this expedition. They are actually great for letting blisters air out. Photo: Amy Towell.

Our first order of business upon arriving: make some waffles. We were told that food supplies were low, so we had brought oil, pancake mix, peanut butter, jelly, brownie mix, freshies (broccoli, cauliflower, apples, pears, cheese, hummus and carrots), and probably some other stuff. Needless to say, our packs were heavy! Our first batch was reminiscent of grilled cheese with fresh sliced tomatoes. They were delicious. All the fresh food was a nice change of pace from the canned goods that we typically eat at main camps.

A photographic summary of life at Camp 8: radio, coffee, power stances and waffles atop the roof. From left to right: Danielle Beaty, Bryn Huxley-Reicher, and Avery Stewart. Photo: Amy Towell.

Unfortunately, the weather was quite cold and misty that first night, so we slept inside. On the plus side, we slept great knowing that we were not going to get the standard 0730 wake up call for 0800 breakfast; we were on our own schedule. Our first radio check of the day was at 0845, so we got an extra hour of sleep! I had big plans to nap a lot while at Camp 8, but that did not happen. After our morning waffles (pumpkin, chocolate chip with pears), Dani and Avery climbed Mount Moore while Bryn and I got busy cleaning up camp. There was a large pile of old insulation that had been subjected to the weather for who knows how long. With my handy surgical gloves, I carefully laid out all of the insulation so it could dry and later be disposed of. After the morning chores, Bryn and I got busy washing ALL of our laundry. Hauling our dirty clothes up to Camp 8 also added a considerable amount of weight to our packs, but it was worth it.

The author amidst the drying insulation and deteriorated burlap. Photo: Amy Towell.

Lunch consisted of broccoli, cheese and cornmeal waffles topped with even more sautéed broccoli. They were fantastic! Just look at that melted, oozing cheese (see picture below). After lunch, I monitored the radio and let my feet rest, while Dani, Bryn and Avery scouted the route we had set the day before. Some of the crevasse crossings had opened up even more, so the route was adjusted slightly and flags were placed for easy navigation. While the gang was out, I received a radio call from Camp 18 informing us that the “fancy dinner” was moved to that night and that we would miss it. We were all pretty bummed since we would have originally made it back in time for the festivities: dressing up, dancing and hamburgers!

Our first dinner: cheesy, broccoli waffles. Photo: Amy Towell.

We decided to have our own fancy dinner and celebrated by making our best waffles yet. We sautéed broccoli and cauliflower and then mixed that into the batter with cheese. To top the waffles, we made BBQ chicken and two over easy eggs. We had precariously brought two eggs with us with intentions of using them to make brownies. We hadn’t had a fried egg for nearly two months, so they were reallocated for dinner, which really fancied things up. Bryn decided to go all out and made some baked beans and pineapple to top his waffle, too. I literally spilled the beans all over the floor in this process. Cleaning them up actually gave the floor a nice “waxy” shine. We ate our waffles on the roof and completed our nightly radio check-in before hiking up Mt. Moore for the sunset. We felt fortunate to see the sunset because Camp 18 was stuck in the clouds, yet we were above them. We had tried to make brownie waffles for the sunset jaunt, but they didn’t really turn out too well. We spent awhile sitting atop Mt. Moore, taking in the scenery. It is arguably one of the best views from the icefield. With the clear skies, we could see our entire summer traverse, which was super cool and really put perspective on how far we skied this summer. We could see Split Thumb, the peak near Camp 17, where we started. We could see the Taku Towers, near Camp 10. We could see Camp 18 and also the valley where Atlin Lake is situated, where our journey would come to an end in a couple short weeks. We could also see Mt. Fairweather, which is quite far away and impressively large, sitting at roughly 15,000 feet.

Our fancy dinner: A waffle with sauteed broccoli and cauliflower with melted cheese, BBQ chiken, pineapple and an over easy egg to top it off. Photo: Amy Towell.

Bryn standing atop Mt. Moore at sunset. Photo: Amy Towell

That night, we slept atop the roof and were pleasantly surprised with a northern lights show. The aurora forecast was only a three of seven, so we did not expect to see any activity. Bryn and I had never seen them before, so we were in awe, to say the least. Avery, who is from Juneau, said that they were hands down the best three-of-seven aurora he had ever seen and probably the best he had ever seen in general.

The next morning, we climbed Mt. Moore a couple more times (five in total for the duration of our stay) and got busy tidying up camp for the next crew to arrive later that day. We also made our last batches of waffles. One batter consisted of cold brew coffee (in place of water) with chocolate chips and roasted coconut flakes. It was easily my favorite waffle. The other batter consisted of pumpkin, oats, chocolate chips, apple, pear, cinnamon, and brown sugar. It was also delicious. We had a lot of batter so these were also made for lunch before we departed. In the end, our group ate a total of 34 waffles during our stay! We left Camp 8 a bit later than we had hoped for, but our next mission was in sight: get back to Camp 18 for dinner at 1900. We cruised back in a swift two hours and made it with 15 minutes to spare. Mission success!