Written by Sarah Bouckoms, with contributions from Lindsey Nicholson and Gabrielle Gascon

For the past two years, JIRP has had more female students than male students. In addition, this year’s field staff and faculty include many powerhouse females. The notion that science is a male-dominated field may still be true in some areas, but not at JIRP. JIRP’s focus is on science and outdoor learning, regardless of gender, race, religion, or sexual orientation/identification. In this blog, JIRP participants Lindsey Nicholson, Gabrielle Gascon and Sarah Bouckoms write on their experiences as women who have worked to attain advanced science degrees.

Lindsey Nicholson is a post doctoral researcher at the University of Innsbruck joining JIRP for four weeks as a visiting faculty member. Lindsey writes:

I'm happy to say that I have not felt discriminated against because of my gender in any way in my career so far. In fact, it seems more common at present to see job advertisements which state that preference will be given to suitably qualified women in order to achieve gender equality in the composition of faculty and staff. Similarly, my current research grant is specifically targeted to women in science, which gave me a better chance of winning the funding. Clearly, although I would prefer to see a simple meritocracy determine the allocation of funding and appointments, I am not above taking advantage of these “positive” gender discrimination tactics that are currently in place. My perception is that current academic faculty in Earth sciences is still strongly dominated by men, but that the cohort of upcoming young scientists is increasingly equally made up of men and women, and in the future I expect that gender will not play any role in appointing scientists or allocating funding money.

That said, I am pleased to see so many young women participating in JIRP, particularly because the combination of group expedition and scientific endeavor encourages all participants to see themselves as equal parts of a whole. Each member has something different to bring to the group and all contribute to the group well-being and scientific success.

JIRP is a particularly powerful program as the expedition focus means that people have to take both individual and collective responsibility for their safety and that of the group. I am concerned that it is not uncommon to observe in science (and in wider society) that women do not take up leadership positions as readily as men, and while I do not wish to take away from instances of great leadership from men in science and society, I think this imbalance is a pity and a potential loss to the community. So, seeing both young men and women filling leadership roles at JIRP, and both male and female students working and cooperating on an equal footing in all the activities of JIRP is a great pleasure.

I hope that I can serve as a scientific role model here at JIRP and play a part in stimulating the participants to be interested in science and the environment, and believe that they can have important roles to play within these spheres of our society.

Gabrielle Gascon also joins us as a visiting faculty member for four weeks from Camp 10 to Camp 18. Gabrielle writes:

I am also happy to say that I have not felt discriminated by my gender so far. I’ve had equal opportunity to undertake field work in the Canadian Arctic, and have not felt disadvantaged when applying for scholarships. I think women should not believe that they are disadvantaged compared to men. Ambition, personality and hard work can take anybody far.

Although most faculties in Earth sciences are still male dominated, Undergraduate classes are becoming increasingly male/female balanced. During my Undergraduate studies in Atmospheric Sciences at McGill University, the program had an equal number of male and female students, and the 4th year Undergraduate course in atmospheric modeling I taught at the University of Alberta for the last two years was female dominated. Over the next few years, I believe that this wave of increasing female students will help balance faculty gender ratios.

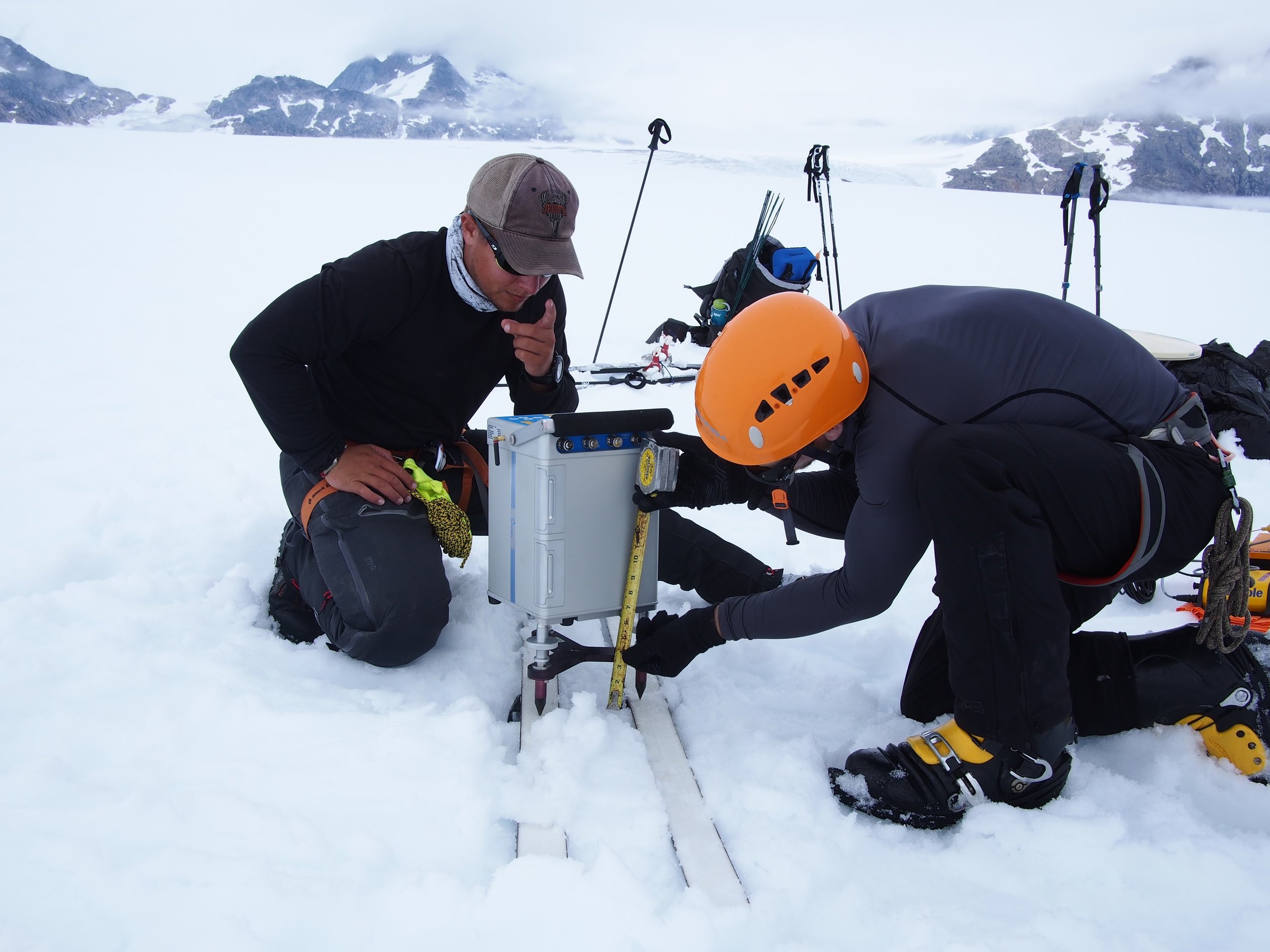

Summer programs like JIRP provide equal opportunities to men and women, and teaches them to work together as a team. Everyone shares daily tasks, goes out to dig (deep!) mass balance pits or cook for 40 people. Most importantly though, everyone feels equal, and I believe that this reflects of the characteristics of the new generation of scientists to come.

Sarah Bouckoms is a JIRP field safety staff member this summer and a high school physics teacher during the school year. Sarah writes:

My mother pursued a career in a heavily male dominated field to become the first female dentist in Waterbury, Connecticut. Just as she followed after her father, I took example from my mother when choosing a profession. While I did not pursue dentistry, rather Physics, I followed her lead to enter a field usually left for the Y chromosomes.

During my Undergraduate and Masters Degree in Physics, I would find myself tallying the head count of male vs. female. In a lecture of 30 or more students, only two or three would be female. At first this ratio made me nervous, but soon it became the normal and I thought nothing of it. From the study groups that formed, not only did I take away some great science lessons, but also both male and female friends. I have had some great professors of both sexes but happened to have most of my supervisors as females.

Next year I am looking forward to teaching high school physics at an all-girls school. I think it will be a great experience to see how the dynamics of a single sex classroom work. I hope that I can be an inspiration to my students motivating them to pursue a field in science. A generation later, Dentistry is now a field with an equal sex ratio, if not more women than men. I feel that transition is starting to take place across the sciences with the Juneau Icefield Research Program setting a great example.

While there is gender equality on the Icefield, this principle does not try to make everyone the same. In fact, each sex is allowed to express themselves however they feel. No one is made to feel uncomfortable by the way they dress, wear their hair or what they choose to shave. Both men and women have shown their excellent skills in the kitchen and in cleaning the lovely outhouses. The dress up parties for dinner are a special celebration enjoyed by all. So it is not at all that women are on the Icefield trying to fit into the mold of a man’s job, but that women are on the icefield doing a job. From pearl earrings to hairy armpits, there is a range of ways that the women on JIRP choose to express their feminine side and all levels are accepted.

In closing, the most important message to take away is that no matter what degree or profession is chosen, the anticipated challenges can be overcome. Anticipated gender inequality in the sciences is not an obstacle that should stand in anybody’s way of pursuing their dream career or following their passion for research in remote and harsh environments. Mental attitude has such a big part in overcoming any challenge regardless of gender. The determination and passion, not the roles traditionally assigned to the sexes, will have the biggest impact on the success of any career choice. Both Lindsey and Gabrielle have expressed their positive experiences as women in the sciences. They are great role models for all the students of JIRP and serve as an inspiration to any women wanting to pursue a career in science.