Annie Boucher

JIRP Senior Staff and Faculty Member

Welcome to the Juneau Icefield Research Program blog! We’re gearing up for the new season: students will soon be connecting with staff mentors to navigate expedition preparation, staff are making plans for staff training week in June, and faculty are sketching out plans for student research projects.

At this time of year, when our new students are preparing for the field season, we know there are a lot of people getting to know JIRP (pronounced “jerp”) for the first time. In the coming weeks, we will use this blog to give you a taste of who will be involved in the expedition this summer, what all goes into expedition prep, and some background on a few of the returning JIRPers who make everything happen. Over the course of the field season - June through August - we will use the blog to post daily updates from the field about what we’re up to. Students will post photos, essays, drawings, and video clips covering both the science research and the day-to-day mechanics of moving more than 50 people across the Icefield.

We have a lot to look forward to! To start, though, here’s a quick and dirty overview of what’s about to happen.

What is JIRP?

JIRP is an expedition-based field science education program. Over two months, we traverse the Juneau Icefield in southeast Alaska and northwest British Columbia, moving between permanent camps while we teach a variety of field research and glacier science topics. Because we are living right on the glacier, JIRP students are immersed in their studies. They don’t just learn about glacier ice flow from a textbook, they go out onto the glacier and explore the real-life markers of flow dynamics from the ice surface, from inside crevasses, from under the ice in sub-glacial caves, and from the bird’s eye view atop nearby mountains. JIRP students spend every waking minute soaking up their surroundings; this leads to a deeper understanding of the environment than any student could get inside the classroom.

Faculty member Billy Armstrong (right, red jacket) holds an evening lecture on ice flow dynamics above the Gilkey Glacier.

Who makes up the JIRP team?

There are three groups of people at JIRP: students, staff, and faculty. At any given time, there are 50-60 people participating in the expedition. Our students are mostly undergraduates, although we often have high schoolers, graduate students, and in-between-schools students as well. Our students come from schools across the U.S. and around the world. Everything that happens at JIRP revolves around student education. This summer we expect to have 32 students, all of whom will be part of the program for the whole field season.

Students Matty Miller (blue jacket) and Tai Rovzar (green jacket) repel into a crevasse and observe their surroundings.

Our staff facilitate field safety and expedition logistics. The Icefield-based field staff spend the first two weeks of the program teaching the students and new faculty required glacier safety skills. For the rest of the season they manage our camps and accompany every group that goes out onto the ice to oversee technical mountaineering challenges and take care of any first aid needs. The Juneau-based staff organize personnel, equipment, and groceries for our helicopters, as well as maintaining daily radio communication with the expedition. This summer JIRP has 12 staff members on the Icefield and two in Juneau, all of whom will work for the whole season.

Field staffer Kirsten Arnell (center, blue jacket) discusses setting routes for rope team travel on the Norris Icefall. The field staff works closely with the students every step of the traverse, teaching them the skills to travel safely through the terrain. Photo credit: Ibai Rico.

Our faculty are researchers, professors, graduate students, journalists, medical doctors, and other professionals. While their backgrounds vary, they share a deep commitment to education and expertise in a field relevant to the Juneau Icefield. They are on the program primarily to teach and while they’re with the expedition all their work includes JIRP students. Faculty rotate throughout the summer; most weeks there are between 5 and 10 faculty members on the icefield.

Student Joel Gonzales-Santiago and faculty member Lindsey Nicholson download meteorological data from a weather station. Photo credit: Allen Pope.

When does JIRP happen?

JIRP is a summer program. Our team is in the field from mid-June through mid-August. The program has been running on this schedule every year since 1949. For more on the history of JIRP, check out our history page and stayed tuned for some JIRP legends to be posted to the blog this spring and throughout the summer.

On clear nights toward the end of the summer JIRPers often sleep outside. Everyone falls asleep around 11:00 pm when it’s getting dark, but it’s not uncommon to wake up three hours later to shouts of “Lights! Northern lights!” Photo credit: Brad Markle.

Where are we working?

The Juneau Icefield is one of the largest icefields in North America at 3,700 square kilometers, covering an area a bit larger than the state of Rhode Island. An icefield is a collection of several contiguous glaciers that flow more or less outward from an area of high snow accumulation. The ice surface of an icefield is low enough that the glaciers flow around, not over, the highest mountains (distinguishing it from an ice cap). The Juneau Icefield straddles the border between southeast Alaska and northwest British Columbia. The western side of the Juneau Icefield abuts the city of Juneau, AK - our students begin their traverse hiking just beyond the Home Depot parking lot. In contrast to many icefields of a similar size, proximity to Juneau makes the logistics of JIRP relatively easy.

The hike down to camp for dinner. At the top of the rocky hilltop in the fore ground you can pick out the buildings of our largest camp. Beyond camp, Taku Glacier flows from right to left in front of the distant Taku Towers. Photo credit: Kenzie McAdams.

JIRP maintains several permanent camps across the Icefield; we are based out of these for most of the summer. Our large camps include bunk room housing for all 50-60 members of the expedition, cooking facilities, outhouses, generators, and lecture space. All permanent structures are built on the bare rocky hilltops above the flowing glaciers. The buildings are modest and space is sometimes tight, but it makes all the difference for us to be able to get out of the weather at the end of the day.

Our last large camp, near the divide between the U.S. and Canadian side of the icefield. Photo credit: Kenzie McAdams.

Why study the Juneau Icefield?

People study the Juneau Icefield for a host of reasons. Geologists seek information about the complicated tectonic and geologic history of Alaska. Biologists examine the flora and fauna of the rocky mountain islands isolated by the flowing ice. Physicists use seismic data to look into the ice itself to understand how the glaciers flow.

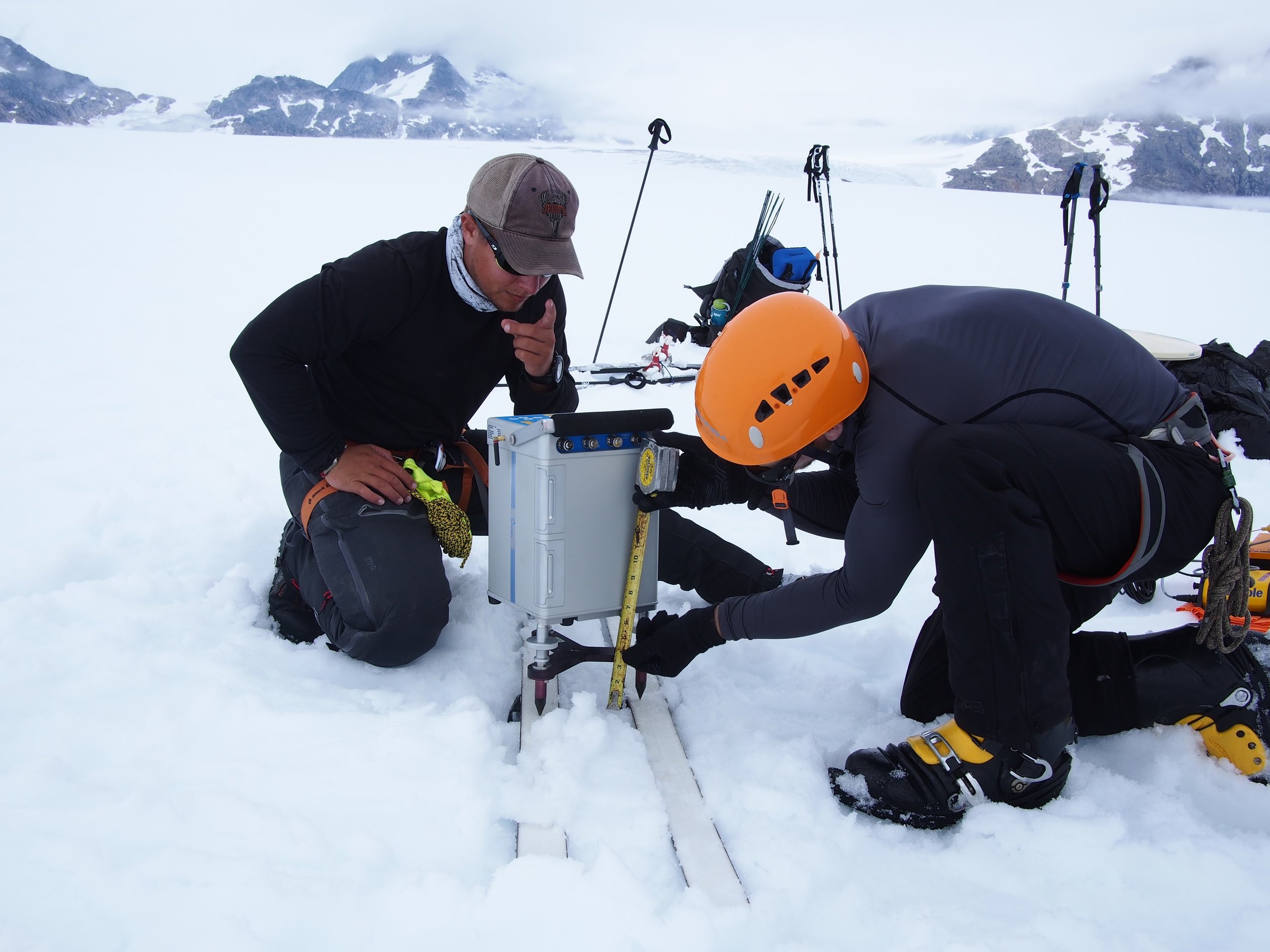

Students DJ Jarrin and Riley Wall set up the delicate gravimeter. The gravimeter measures tiny anomalies in the local gravity, which the students use to deduce information about the bedrock buried beneath almost a mile (1500 m) of ice. Photo credit: DJ Jarrin.

Glaciers are also a “hot topic” right now because of climate change. Glaciers form and flow in areas where annual snow accumulation is high enough that substantial snowpack survives the summer. Because they rely on the snowpack, glaciers are sensitive to two central pieces of climate: temperature and precipitation. Measuring and observing different aspects of glaciers can tell us about past and present trends in temperature and precipitation. Climate research is a central component of the JIRP curriculum, but it is far from the only topic we cover.

Students Kate Bollen, Kristen Lyda Rees, and Louise Borthwick measure the density of the snow accumulated over the past year. Even at the end of the summer the last year’s snow accumulation is often 4-6 m/13-20 ft. deep high on the icefield. Measurements of the each year’s snowfall are compared with a continuous dataset that stretches back to the 1940s. Photo credit: Victor Cabrera.

That’s all we’ve got for now. Blog posts will be published periodically this spring and almost daily during the summer on every aspect of working and living on the Juneau Icefield. In the meantime, we hope this gives new students, their friends and family a basic idea of what to expect in the coming months.