Matt Beedle

Director of Academics and Research

Today is a special day on the JIRP calendar. As you read this, the 2017 JIRP staff team – with excitement for the new field season despite the weather – is hiking to Camp 17 for “Staff Week”. These 12 days of opening JIRP’s first main camp, wilderness first aid training, glacier travel/rescue training, and (let’s be honest) at least a few runs on the Ptarmigan Glacier to test skis and snow conditions, kicks off the field season. It establishes more than physical goals and hard skills, however. The culture, community and camaraderie of JIRP 2017 begin to form today. While each season is unique, there are threads of commonality that span the many generations of JIRP field seasons and individual JIRPers. One of the most powerful threads in each field season is that of mentorship.

We’ve done quite a number of short pieces on JIRP history in recent years (see some of them here, here and here), but a component of JIRP that hasn’t been communicated in particular is the long history of mentorship. Post-JIRP, students regularly comment on the value of having tremendous access to inspiring staff members and faculty. The often cheek-by-jowl conditions of a JIRP camp, skiing for hours in a driving rain, discussion of ideas, problems and dreams allow for JIRP students to get to know one another well. These moments, however, are also shared with faculty and staff, moments that have been shared on the Juneau Icefield for decades. The JIRP story begins in the 1940s, but a chain of mentorship can be traced back in time even further.

John Muir first ventured to Alaska in 1879 for the first of his fabled canoe journeys through southeast Alaska. He wasn’t the first to journey here, as western sailors had been poking into the bays and fjords of southeast Alaska since Chirikov’s voyage of 1741, and the Tlingit people had called this part of the world home for many thousands of years prior. Muir’s 1879 voyage, however, did initiate a western investigation of the glaciers of southeast Alaska, enabled by his Tlingit guides.

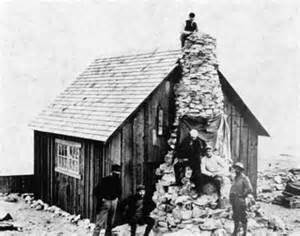

John Muir and Reid's team at the Muir cabin in Glacier bay, 1890. Source: National Park Service

On a subsequent trip to southeast Alaska in 1890, Muir spent time in Glacier Bay with Harry Fielding Reid and a team of scientists investigating the dynamics of Muir Glacier. Reid’s subsequent Variations of Glaciers work would be a foundational effort for the World Glacier Monitoring Service of today. One of the individuals that Reid mentored and inspired was William O. (Bill) Field, known as one of the founders of modern glaciological study in North America. For his 1941 expedition to southeast Alaska, Field inquired with Bradford and Barbara Washburn in looking for a capable field assistant.The Washburns pointed him to Maynard Miller, a Harvard undergraduate who had been on their expedition to Mount Bertha the previous year. Field and Miller’s shared field experiences in 1941 and subsequent years gave rise to this important new direction to explain glacier behavior:

“It became fairly clear to us in 1941 that a full explanation was more likely to be found in the upper elevations rather than at the terminus.”

Maynard Miller (right) explores the remnants of the Muir cabin in Glacier Bay during the 1941 expedition led by Bill Field. Source: Field, William Osgood. 1941 No Glacier: From the Glacier Photograph Collection. Boulder, Colorado USA: National Snow and Ice Data Center. Digital media.

After a few years of aerial reconnaissance and further investigation of the termini of glaciers of southeast Alaska, followed by a first exploration of the “high ice” of the Juneau Icefield in 1948, JIRP the annual field expedition began in 1949. It has continued ever since, and this chain of mentorship has been ongoing, from Field and Miller, to individuals such as Ed LaChapelle, Austin Post, Kurt Cuffey, Christina Hulbe, Steven Squyres, Kate Harris, Alison Criscitiello and many hundreds more. From this annual traverse of the Juneau Icefield, dreams, careers, adventures are launched.

It is challenging to keep track of the inspiring work that recent JIRP alumni are taking on, let alone the many hundreds who have come before them. A part of this inspiration has come from interactions with JIRP mentors: the long ski traverses filled with academic discussions, songs, and stories; the hardships and smiles shared in the field and back at camp; the guidance during the season and in the years that follow. With this view back at the long chain of mentorship through many decades of exploration of the icy corners of southeast Alaska, it is exciting to think of the JIRP staff of 2017. Slowly making their way to Camp 17 today, hiking in the literal and figurative footsteps of the many hundreds before, they are setting in motion the foundational community of JIRP 2017 - the community of staff, faculty and students that will continue this chain.

Note: Thanks to Bruce Molnia for being a JIRP mentor of mine and for pointing out the linkages back in time from Mal Miller, to Bill Field, to Harry Reid, and to John Muir.